God also Speaks Ilocano: A Short Account of the Translation of the Bible into Ilocano

|

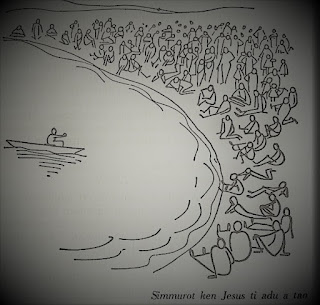

| Illustration: Anne Marie Vallotton Naimbag a Damag ti Agdama a Panawen |

As the Year of Ecumenism is drawing to a close, and as the Quincentenary of Christianity in the Philippines is at hand, I thought that one concrete example of ecumenism in the Philippines is the Bible's translation into my native tongue (Ilocano or Iloko).

Let me share this short account (some personal) of the translation of the Ilocano Bible, which was first presented at the the symposium, "History of the Filipino Bible," on March 2, 2016, at the Divine Word Seminary, Tagaytay City. I also presented it last January (2020) with the participants of the Biblical Apostolate convention of the Diocese of Antipolo organized by Mr. Resty Adoremus.

Since I'm currently discussing with my students at the Divine Word Seminary-Tagaytay the Transmission of the Biblical Text (including Translation, for the course Introduction to Sacred Scriptures), this piece is also worth sharing with them.

"Siak ti Dalan ti pudno ken ti biag awan ti mapan ti Amak no di magna kaniak."

What a beautiful and warm Ilocano translation of John 14:6, "I am the way the truth and the life, no one comes to the Father except through me."

God also speaks Ilocano, or as Dr. Ebojo says in his book's title, God Loves Pinakbet too (2009).

The Ilocano Popular Version (Naimbag A Damag Biblia), 1973/1983

The first Ilocano Bible that I saw, possessed, and grew with is the Ilocano Popular Version of the New Testament with the loveable, and now iconic, drawings of the Swiss-born artist Anne Marie Vallotton (see the image above).

It opens (in the Introduction) with powerful words: "Naimbag a damag--daytoy ti kasapulan unay ti lubong! (Good News--this is what the world needs now!).

This new translation was published in 1973, a year after the declaration of Martial Law. I was then in Grade 1. It was sold for 2 pesos (3 pesos against a US dollar for the exchange rate that time).

In 1981, after eight years from its publication, the publisher, the Philippine Bible Society (PBS), had complained that there were still many unsold copies in their bodega. The PBS had printed 100,000 copies, but the Ilocano reception of the Bible was "cold," so the PBS had to donate 30,000 copies to the John Paul I Biblical Center in Vigan to be distributed almost for free!

How can you sell the Bible to the Ilocano, who is nainot and nakirmet (in good Tagalog, makunat)?

After ten years, though, in 1983, a few months before Ninoy Aquino was assassinated, compete Ilocano translation of the Bible (with the Deuteronocanicals), was launched. This event was held at the Cathedral of Vigan in Ilocos Sur, and most likely, the grandest launching of a bible to occur in the country at that time. The Archbishop of Nueva Segovia presidever the Eucharist. The big guns of the PBS were there. The cathedral was jam-packed. I was in the fourth year highschool then at the Saint Joseph Seminary in Abra. The whole seminary was bused into the place to sing in the choir.

That translation called Naimbag a Damag Biblia (Good News Bible), the Ilocano Popular Version, is the Ilocano Bible until today. It is the Bible used in our Lectionary.

The Union Version (Ilocano Bible of 1909)

|

| Credit: E. Ebojo |

In 1909, just 13 years when the Philippine Revolution broke out, the SVD missionaries arrived in the Philippines, particularly in Abra. The two pioneer missionaries were tasked to check the advances of the Aglipayans and the Protestants, whom the Bishop of Vigan described as "endeavoring to pervert the inhabitants of that region" (Layugan, 52).

It was not, therefore, the best of times for Christians to work together to translate the Bible into one of the languages of the Revolution.

Whatever political and economic motives the American and English-speaking Protestants had, they went ahead to sponsor a local translation.

In the vision of the United Bible Societies at that time and still is, it states: "We believe the Bible is for everyone so we are working towards the day when everyone can access the Bible in the language and medium of their choice."

The Spanish-American War broke out in Aug 1898, and Commodore Dewey consequently declared Manila as an open city.

At that time in Madrid was an Ilocano man of letters, Don Isabelo De Los Reyes, Sr, exiled due to his involvement in the Revolution. He would turn to be the founder of the Aglipayan Church (1902).

This young man of 34 years old from Vigan got a request from the British and Foreign Bible Society to translate the Bible into Ilocano. Before the end of 1898, an Ilocano translation of Luke was being shipped to the Philippines. Don Belong, as he was fondly called, based his translation on a Spanish Bible (Laeda, 41).

After three years, he also finished translating the Acts of the Apostles. Don Belong's translation was to be the seed of the first Ilocano Bible, which would be completed (OT) in 1909.

|

| Credit: E. Ebojo |

Thus, it took them only 11 years; the basis was the American Standard Version (1901).

The local translators and reviewers were "big time" in their own right. For instance, apart from Isabelo de Los Reyes, there was Professor Ignacio Villamor, the best Ilocano scholar at that time. He studied in Vigan Seminary and became the first Filipino president of the University of the Philippines.

The first Ilocano Bible, called the Union Version, is a product of interdenominational cooperation.

However, there was only one Roman Catholic in the group, that is (presumably) Villamor.

Thanks to the American Bible Society, the first complete translation of the Bible in Ilocano, "the most virile of the languages of the North," was published in 1912.

The Ilocano Bible of Fr. Lazo (1920)

In 1920, however, Fr. Melanio Lazo, a Catholic priest from Ilocos Sur came out with his Ilocano translation of the Gospels and used the Latin Vulgate and a Spanish version (Scio) as his base.

This translation also appeared in the "most influential" Ilocano Catholic magazine at that time, Amigo del Pueblo (1925) published by the Catholic Trade School press owned by the SVD missioanries.

Fr. Mariano Pacis from Ilocos Norte, from 1942-1948, also translated the Sunday Gospel readings and the Wpistles, including the Acts – and was published as well by the Catholic Trade School pres. He completed the whole NT in 1969 (published by the Society of Saint Paul).

In the foreword of the Ilocano translation of Fr. Lazo, Fr. Pacis gave us a hint as to why such translations were done: "because of the cruelty caused by the Bibles distributed by the enemies of the faith" (Laeda, 55; cf. also the translation of the Aglipayan Santiago Fonacier in 1969, unpublished).

Ecumenical Effort

The Roman Catholic authorities had come to PBS to ask permission to use their Bibles in the Liturgies, and PBS proposed to work together to come up with new translations.

Thus a committee was formed coming from different denominations – two were Roman Catholics – Mr. Peter La Julian (known for his works in the Bannawag Ilocano magazine) and Fr. Godofredo Albano. The UBS project coordinator was Dr. Noel Osborn from the United Evangelical Brethren.

|

| Translators of the Ilocano Bible, 1983 Credit: E. Ebojo |

This new translation would see its revision in 1996, which includes the Deuteronanical books' rearrangement following the Catholic listing.

|

| Team for the Revision of the New Ilocano Bible (1996 Credit: E. Ebojo |

Gone gone was the atmosphere of animosity and suspicion on the part of the Roman Catholics—the spirit of Vatican II and its document, Dei Verbum (1965) blew where it willed.

God also Speaks Ilocano

In a way, we can also say it was born in the violent aftermath of the Philippine Revolution; and a Martial Law baby at that.

Thanks to the "Bible Christians, the Protestants were called then, who had given a lot of time, energy, and money. After more than 300 years of Christianity (from 1521 to 1909), we have an Ilocano Bible.

After 74 years later, we got a new and beautiful, dynamic translation of the Bible in Ilocano used in our Catholic liturgies until today.

However the Bible was a late-comer, it came to the Philippines in a different but equally beautiful way.

The Word of God found its expression in the Ilocano Doctrina Christiana of 1621; the metrical Ilocano chant in the poetic and metrical retelling and chanting of the passion of Jesus in the Ilocano Pasion of the 19th century, the numerous prayers, novenas, rosary, and songs in the popular devotions practiced in and outside the church, the images of saints, stations of the cross, and processions (libot).

All of all these prepared the way for God to speak in Ilocano.

Comments

Post a Comment