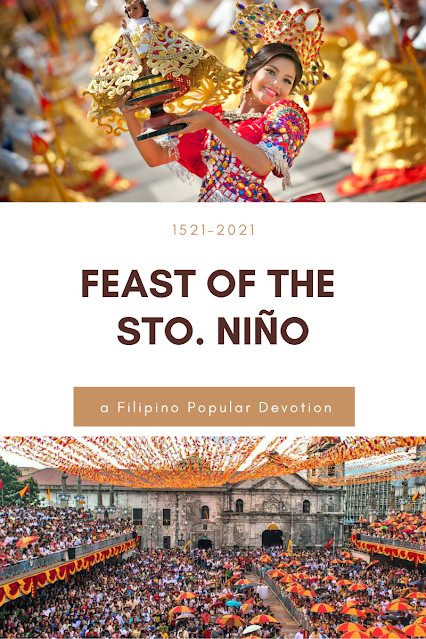

Sto Niño, 500 years ago, and the "Wunderkind" in Isaiah

Santo Niño

It was 500 years ago. Magellan came to the Philippine Islands in 1521. His chronicler, the Italian Antonio Pigafetta, was supposed to have given a gift to the local queen named Doña Juana. It was an image of what was later on called “Santo Niño" (Holy Child)

When the Spaniards returned in 1565, they found an image of it (same image?) inside a house, adorned with flowers and enthroned on an altar. Christianity survived even without the "foreign missionaries." And it was in the form of an innocent veneration of an image.

A legend today would even claim that locals had addressed the image as “Bathala” (the old Filipino name for God).

The Readings for the Feast

All three Readings allude to the child as its theme: "Unto us, a child is born" (Isaiah 9:1-6), "adoption" (Ephesians 1:3–6, 15–18), and children to whom the kingdom of God belongs (Mark 10:13-16). It is the "child" in Isaiah that is enigmatic.

The Wunderkind in Isaiah

The prophet Isaiah speaks of “a child is born to us… on whose shoulders dominion rests… and whose name is ‘Wonder-Counselor, God-Hero, Father-Forever, Prince of Peace’” (9:6).The context of Isaiah 1:1-6 is not so clear although biblical scholars share some reasonable suggestions.

The text is likened to ancient Egyptian rituals celebrating the accession of a new pharaoh. Such enthronement is usually accompanied by the giving of throne names by the assembly of the gods and goddesses. The rite ends with the divine assembly adopting the king as their child.

Notice the four titles above conferred on this wonder-child.

A few suggestions have also been made as to the identity of the mysterious child “who is born to us” and who becomes a ruler.

One candidate is the child of king Hezekiah of Judah. Hezekiah's reign is dated as 715-687 BCE.

Both biblical and extra-biblical sources attest to the war strategy employed by Hezekiah against the invading Assyrian army led by Sennacherib (705 BC - 681 BC).

In that invasion, through Hezekiah’s negotiation and prayer, Jerusalem was spared from apparent destruction (2 Kings 18-20, Isaiah 36-39).

This prophetic text also speaks of oppression in the familiar images of servitude - yoke, pole, and rod (Is. 9:3) - a “yoke placed on the neck” (Isa 10:27); the pole is used to strike the shoulders (Isa 10:24), and the rod is an instrument for beating prisoners into subjection (Isa 10:24).

The identity of the oppressor in this context is not also specified but interpreters point to a brief period of foreign rule by the Assyrian empire, perhaps during the campaign of the Assyrian king Tiglath-Pileser (744-727 BC., see 2 Kgs 15:29) and later on continued by Shalmaneser V (726-727 BC).

Oppressive measures in those days included the payment of tributes to the empire, and sending the leaders into exile.

In any case, the prophet Isaiah portrays in symbolic imagery the coming liberation of its people from oppression: the transition from the land of gloom (9:1) - a figurative language for the underworld (see Job 10:21-22), to a place of brilliant light.

In other words, there will be an end to hostilities, war is abolished and replaced by “abundant joy”.

There will be peace (shalom) characterized by “judgment and justice” (mishpat and tsedaka, see 9:6).

All of these magnificent events will happen because of the birth of a wonderful child.

The fact that such great hope would rest on a child would be a factor for Christians to identify the child with Jesus (note that this text is read at Christmas Midnight Mass as well) - an allusion that is immortalized in Handel’s Messiah (Part I - “For unto us a child is born”).

The Child as Divine

It is unusual in the Bible and even in the ancient Near East that a deity assumes the form of a child.

In contrast, when gods are described, images that characterize strength and power are used.

In the Canaanite religion, the supreme god, called El, bears the title of “the Bull”. The goddess Anath takes the form of an eagle. The god Baal is associated with thunder.

In the Bible, God is at times compared with a lion (see Amos 1:3) or an eagle (Exod 19:4), even with a mother (Isa 66:13), but rarely with a child. The reason is that a child is a symbol of weakness.

That our God would assume the form of a child speaks then of his humility and solidarity with those who are weak.

St. Paul in his letter to the Philippians articulates best this divine humility and solidarity (called kenosis in Greek):

Christ Jesus, who, though he was in the form of God, did not regard equality with God something to be grasped. Rather, he emptied himself, taking the form of a slave, coming in human likeness; and found human in appearance, he humbled himself, becoming obedient to death, even death on a cross" (2:6-8).

Comments

Post a Comment