LECTIO DIVINA

|

| Source: Rocio Garcia Garcimartin, La Lectio Divina (2011) |

Lectio Divina: A Critical and Religious Reading of the Bible

Serious historical-critical biblical

study and the devotional use of Scripture need not be viewed as opposites. In

fact, they can and should enrich one another.

Lectio Divina provides a good framework for doing so.

By Fr. Daniel J. Harrington, S.J.

The late Fr. Harrington wrote numerous

scholarly works, including a commentary on the Gospel of Matthew in the Sacra

Pagina Series. He was a professor of the New Testament at Boston College. He

served as editor of New Testament Abstracts from 1972 until his death in 2014.

This post was published on the

now-closed HuffPost on Oct 12, 2012

In The Bible and the Believer, Marc

Z. Brettler, Peter Enns, and I explore how biblical scholars from different

traditions--Jewish, Evangelical, and Catholic--integrate their

historical-critical learning with their ongoing religious commitments. The word

"historical" means reading the text in its ancient context, and

"critical" means using the power of reason and judgment. Here I want

to illustrate with reference to Exodus 3:1-6 how those in the Catholic

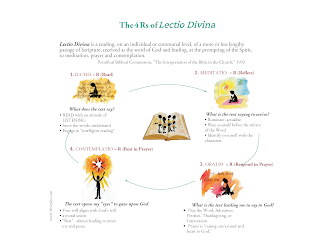

tradition might do so. The framework is lectio divina ("sacred

reading"), an ancient monastic practice that can be adapted to include

both historical-critical and religious readings of texts. It has four steps:

reading, meditation, prayer, and action.

Reading

Here the question is, What does the text

say? The context of Exodus 3:1-6 is the account in Exodus 3-4 of Moses' initial

encounter with the Yahweh, the God of Israel. It comes after the narratives of

his birth and infancy, as well as of his murder of an Egyptian and flight to

the land of Midian. The text according to the New Revised Standard Version

reads as follows:

"Moses was keeping the flock of his

father-in-law Jethro, the priest of Midian; he led his flock beyond the

wilderness, and came to Horeb, the mountain of God. There the angel of the Lord

appeared to him in a flame of fire out of a bush; he looked, and the bush was

blazing, yet it was not consumed. Then Moses said, 'I must turn aside and look

at this great sight, and see why the bush is not burned up.' When the Lord saw

that he had turned aside to see, God called to him out of the bush, 'Moses, Moses!'

And he said, 'Here I am.' Then he said, 'Come no closer! Remove the sandals

from your feet, for the place on which you are standing is holy ground.' He

said further, 'I am the God of your father, the God of Abraham, the God of

Isaac, and the God of Jacob.' And Moses hid his face, for he was afraid to look

at God."

The first step in analyzing a biblical text

is literary criticism, that is, examining the words and images (the mountain of

God, the angel of the Lord, the burning bush, the Lord, holy ground), the

characters (Moses, the Lord), the plot or structure, the literary type or form

(theophany, or divine revelation), and the message (dynamics of religious

experience, encounter with the sacred).

The text is a perfect example of the mysterium

tremendum et fascinans of religious experience. It begins in Moses'

curiosity, which demands further inspection, involves a call to personal

relationship, leads to a recognition of the sacred as different from the

profane, features the identification of Yahweh (the Lord) with the God of the

ancestors, and ends with Moses' reverent fear. His encounter is fascinating,

mysterious, and overwhelming.

Behind the text lays a host of (most

unresolved) historical questions. What does the divine name YHWH mean? In 3:14

Moses is to tell the Egyptians that "I am who am" sent him. The name

may refer to this God as creator: "the one who causes to be." Or it

may be a way of saying, "Read on and you will see." Medieval

philosophers found in this text the basis for understanding God as pure being.

This raises the further questions whether Yahweh may have been the tribal god

of the people of Midian and Moses' father-in-law, and how Yahweh related

historically to the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob.

In scholarly circles the account in Exodus

3:1-6 is customarily assigned to the J ("Yahwist") source, because it

features the divine name "Yahweh." That source, while very early

(10th-9th century), is still hundreds of years distant from Moses. How can be

sure what comes from Moses? What really happened? There are many different

answers to these questions, and they are debated vigorously. The believer has

to recognize these questions, without necessarily being overwhelmed by them, since

what is most important is the text as it stands.

Meditation

Here the question is, What does the text

say to me? Of course, Exodus 3:1-6 may say many different things to many

different people. For believers it is not simply a relic of the past or even a

classic text. It is these things but more. It is a sacred text. Some refer to

it as "the word of God." For thousands of years people have read,

mediated, and prayed over this text.

The purpose of reading such a biblical text

is to open one's mind and heart to the religious heritage of Judaism and

Christianity. The kind of literary and historical analysis illustrated above

can help to uncover the riches within the text. When meditating on a biblical

passage, some find it helpful to enter the scene by way of their imagination.

Think of yourself on Mount Horeb beside Moses. What do you see? What do you

hear? What might you smell, touch, or taste?

Longtime believers may find in this text

confirmation of their own religious experiences, while recent converts might

use it to connect their experiences with the great tradition of biblical call

stories (Moses, Isaiah, and Jeremiah). Some may focus on the symbol of the

burning bush, while others may reflect on the text's revelation of God or

empathize with Moses' development from curiosity to "fear of the

Lord" (a good thing in the Bible).

In my own life this text has been very

influential. As a boy I stuttered. When I heard that Moses stuttered, I looked

up Exodus 4:10, where Moses says to God, "I am slow of speech and sloe of

tongue." But I found much more than that. Reading the whole of Exodus 3-4

introduced me to the dynamics of religious experience, and eventually led me to

become a Jesuit priest and a specialist in biblical studies. Whenever I find

myself discouraged, I go back to this text and find in it encouragement and

direction.

Prayer

Here the question is, What do I want to say

to God on the basis of this text? Many Christians and Jews use biblical texts

as starting points in their prayer. With regard to such a rich text as Exodus

3:1-6, it may be sufficient to say "Wow." Many readers may want to

thank God for their own religious experiences, and compare and contrast them

with that of Moses. Other who feel less centered may ask God for help in

enriching their relationship with God.

Contemplation/Action

Those who pray with Scripture often find

the exercise so engaging that they want to stay with the text, further relish

its details, and integrate it into their piety. This is contemplation. Still

others find that their engagement with the text may prompt them to take action:

Resolve to pray more; join a Bible study group; work on some problem or

obstacle in their life; engage in interreligious dialogue; or be more active in

the community.

Serious historical-critical biblical study and the devotional use of Scripture need not be viewed as opposites. In fact, they can and should enrich one another. Lectio divina provides a good framework for doing so.

---

Cardinal Martini on Lectio Divina

You may also download here an article on Lectio Divina by the late Cardinal Martini, one of the bishops whose lectio divina sessions were well-attended, especially by the youth at the Cathedral of Milan. Click to download.

Comments

Post a Comment